Whether International Law is Really a Myth?

During my student years, while studying international law, certain definitions ceased to be mere tools for examination preparation and instead became enduring memories of intellectual struggle and conceptual reflection. One such definition was offered by the renowned jurist Thomas Erskine Holland, who described international law as “the vanishing point of jurisprudence.” According to him, international law lacks a fully sovereign legislature, a binding system of sanctions, and an enforcement mechanism capable of compelling states to comply with rules. From this perspective, international law fails to meet the classical standards of jurisprudence.

At that time, this critique unsettled us. It was difficult for a young mind to accept that a discipline regarded as the foundation of global justice could be labelled “incomplete.” This disagreement was not merely emotional; it was supported by historical experience. In the 1970s, the aura of the United Nations genuinely appeared radiant. Newly independent nations emerging from colonial rule, the international human rights framework, the global struggle against apartheid, and the idea of collective security during the Cold War together generated confidence that international law would gradually rise above power politics and evolve into a universal architecture of morality and justice.

However, standing in the world of 2024–26 and looking back, it becomes evident that this confidence is undergoing a severe test of reality. The Ukraine war entering its third year, the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, maritime insecurity in the Red Sea, and the growing dissatisfaction of the Global South all signal that the international order today is leaning more toward an interest-based system than a rules-based one. In a multipolar world, the distribution of power is changing, yet compliance with rules remains uneven.

Against this backdrop, the crisis in Venezuela emerges as a symbolic case. Venezuela is no longer merely a story of economic collapse or democratic erosion. The disputed elections of 2024–25, sustained restrictions on political opposition, widespread migration pressures, and the resurgence of energy geopolitics have collectively raised serious questions about the effectiveness of international law. The United Nations, regional organisations, and international forums remain active, but their roles often appear limited to observation and rhetoric. Decisive intervention capable of producing behavioural change remains rare.

Here, the very weakness identified decades ago by Holland becomes visible once again—the absence of effective enforcement. Resolutions are adopted, condemnations are issued, special envoys are appointed, yet rules acquire real force only when the interests of powerful states are engaged. As power balances shift, the interpretation of norms also changes. Consequently, the same principle—whether sovereignty or human rights—assumes different meanings across different contexts.

In this context, the influence of Donald Trump is not merely a matter of historical memory. The 2024 U.S. elections and the global reactions that followed made clear that “America First” has evolved into a broader international tendency rather than remaining confined to one individual. This tendency includes skepticism toward multilateral institutions, distance from international treaties, and an increasing reliance on sanctions as a primary diplomatic instrument. In the Venezuelan case, this tension becomes particularly sharp, where the language of human rights and the imperatives of energy security visibly collide.

This is precisely where international law appears suspended between theoretical ideals and practical politics. Does sovereignty still retain its absolute and inviolable character? Is humanitarian intervention genuinely universal, or has it become subject to selective morality? Do rules apply equally to all, or do powerful states effectively become exceptions? The global order of 2024–26 appears unable to provide clear and satisfactory answers to these questions.

Yet the hope that emerged during my student years has not entirely faded. Prosecutions before the International Criminal Court, judicial developments in the law of the sea, the growing global discourse on climate justice, and the increasingly organised and assertive voice of the Global South all suggest that international law is not an illusion. It remains a gradual, evolving process—slow, certainly, but not futile.

Perhaps Holland was right in arguing that international law is not “law” in the classical sense. Yet it is equally true that without it, global politics would contract into raw power, military coercion, and economic domination alone. In crises such as Venezuela, Ukraine, and Gaza, the limitations of international law become evident, but so does its necessity. Rules may be fragile, yet the absence of rules proves far more destructive.

Today, when I view those student debates through the lens of the realities of 2024–26, it becomes clear that Holland was not entirely wrong, nor were we students entirely idealistic. International law truly exists in a transitional condition—where it stands simultaneously as the vanishing point of jurisprudence and as a potential foundation for a more responsible and more humane global order.

Ultimately, the question is not whether international law is weak or strong. The real question is whether nation-states will continue to employ it merely as a matter of convenience and interest, or whether they will genuinely shape it into a shared moral responsibility capable of addressing the complex challenges of the twenty-first century—climate change, migration, war, and inequality. In today’s world, the answer to this question will determine the future direction of the international order.

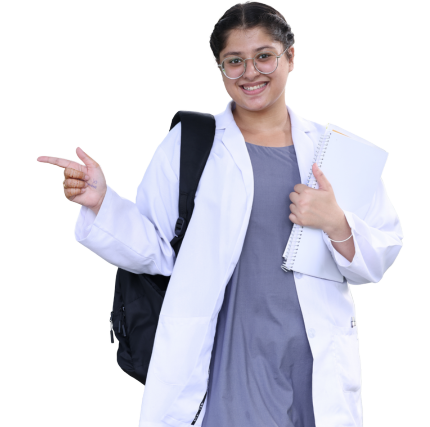

by Prof. Harbansh Dixit